We construct our sentences, our written or spoken speech, as if this distinction between emotive meaning and reference did not exist. When the man said, “That is sublime,” he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall. The form of the sentence is exactly similar to the form of “That is brown,” a sentence which does make a remark about the waterfall, about its colour. Actually, when the man said, “That is sublime,” he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings…. And you will find this confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something; and, actually, we are only saying something about our own feelings. (19-20)

—The Control of Language (1939)

During the Second World War, C.S. Lewis was asked by the University of Durham to present the Riddell Memorial Lectures. Over three evenings in early 1943 (February 24-26), Lewis spoke in the village of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne; the lectures were published in a book later that same year by Oxford University Press, called (after the final lecture) The Abolition of Man. Notably, though, the book has a lengthy subtitle: The Abolition of Man, or Reflections on education with special reference to the teaching of English in the upper forms of schools. While the lectures can be appreciated by anyone, Lewis was motivated to write them because of his concern with how the next generation was being educated — or rather, in his estimation, miseducated.

In the first lecture, “Men Without Chests,” Lewis sees the dangers of a certain approach to the teaching of rhetoric. His example is a passage from a book he refers to merely as The Green Book, not wishing to “pillory two modest practising schoolmasters who were doing the best they knew,” but of course it is easy to uncover that the book to which Lewis is referring is actually called The Control of Language, published several years earlier by Alex King and Martin Kelty. Lewis does not think King and Kelty set out to reject the value of sentimental education, but he fears that children will infer it from The Control of Language nonetheless.

The schoolboy who reads this passage in The Green Book will believe two propositions: firstly, that all sentences containing a predicate of value are statements about the emotional state of the speaker, and secondly, that all such statements are unimportant. It is true that [the authors] have said neither of these things in so many words. They have only treated one particular predicate of value (sublime) as a word descriptive of the speaker’s emotions. The pupils are left to do for themselves the work of extending the same treatment to all predicates of value: and no slightest obstacle to such extension is placed in their way. The authors may or may not desire the extension: they may never have given the question five minutes’ serious thought in their lives. I am not concerned with what they desired but with the effect their book will certainly have on the schoolboy’s mind. In the same way, they have not said that judgements of value are unimportant. Their words are that we ‘appear to be saying something very important’ when in reality we are ‘only saying something about our own feelings’. No schoolboy will be able to resist the suggestion brought to bear upon him by the word only. I do not mean, of course, that he will make any conscious inference from what he reads to a general philosophical theory that all values are subjective and trivial. The very power of [the authors] depends on the fact that they are dealing with a boy: a boy who thinks he is ‘doing’ his ‘English prep’ and has no notion that ethics, theology, and politics are all at stake. (4-5, emphasis mine)

Bad ideas are one thing — bad ideas set before children are another, because children are trusting and also, as Lewis implies, merely trying to get through the studies they have been assigned. Charitable to a fault, though, Lewis argues that King and Kelty’s approach stems from their own misunderstanding of the historical moment:

…I think [the authors] may have honestly misunderstood the pressing educational need of the moment. They see the world around them swayed by emotional propaganda—they have learned from tradition that youth is sentimental—and they conclude that the best thing they can do is fortify the minds of young people against emotion. My own experience as a teacher tells an opposite tale. For every one pupil who needs to be guarded from a weak excess of sensibility there are three who need to be awakened from the slumber of cold vulgarity. The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts. The right defence against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes. For famished nature will be avenged and a hard heart is no infallible protection against a soft head. (13-14)

Put to the test

For the last week, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about Hamilton Hall, the building on Columbia University’s campus that was briefly taken over by pro-Palestinian protestors. At precisely this time 25 years ago, I was probably taking final exams in that building; most of my classes in college were held in Hamilton, and generally, final exams were given in the same classroom. I find it both astonishing and heartbreaking that the extreme actions of an incredibly small number of students have managed to derail the proper business of an Ivy League university in the middle of New York City; classes and exams have been all pushed online, and now Columbia has cancelled the University’s main commencement ceremony. At that event 25 years ago, my fellow graduates and I heard the new medical doctors take the Hippocratic Oath and the main speaker was Muhammed Ali. (I won’t lie; no one was terribly upset that the ceremony was shortened due to the rain.)

In a sad irony, the very students who are being deprived of normal college graduation are the same children whose high school graduation was disrupted if not disappeared by the Covid pandemic in 2020. Despite this — and despite surely a bunch of very angry, disappointed parents who had been looking forward to the pomp and circumstance of commencement — Columbia (among other colleges and universities) seems persuaded that the reputational/security risk of having the ceremonies is too great. While I have no sympathy with either the actions or the cause of the pro-Palestinian demonstrators, I have come to the conclusion that the reason they are throwing pick-me tantrums ostensibly about the horrors of Gaza is because this is what the adults they look up to have told them to do.

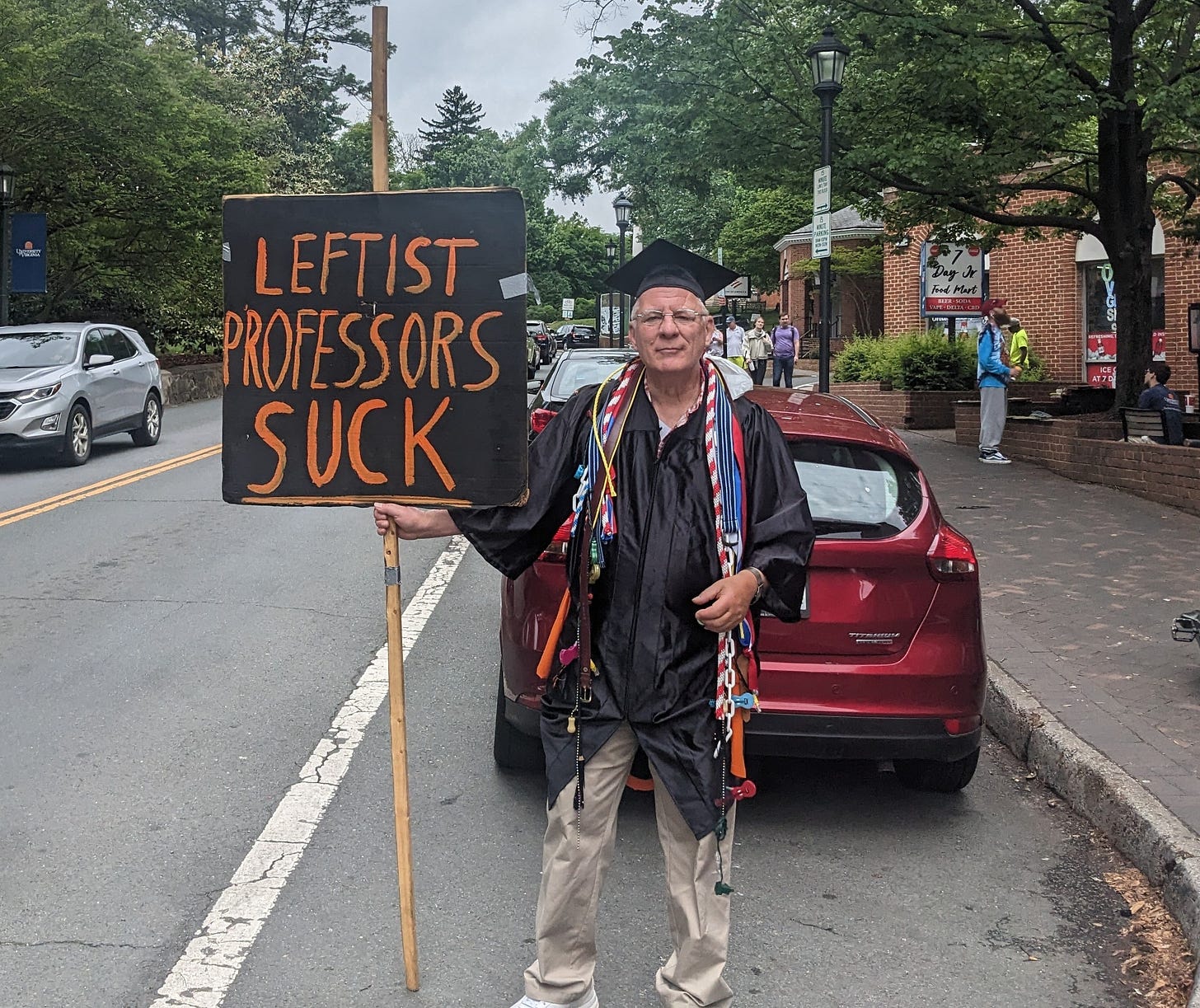

Whatever you think of the political motivations of the Congressional hearings about anti-Semitism on college campuses, it strikes me that the real problem that these college presidents are facing is not the unruly and (in many cases) indefensible behavior of their students. The actual problem that still plagues Minouche Shafik — and I bet will lead to her eventual resignation — is that she is the head of an elite institution that is full of professors who are paid to teach ideas and defend positions that most Americans find reductive, ridiculous, and repugnant — if not all three. In short, the problem is not that a bunch of cosplaying, keffiyeh-wearing Gen-Zers enjoy shouting “from the river to the sea” and intimidating their Jewish classmates; the problem is rather that they are doing so with the full encouragement and approval of the professors supposedly in charge of educating them.

There is plenty of data that confirms that these institutions are ideologically skewed to the political left — but we’re no longer talking about the old school left of defending the interests of the middle class against the depredations of capitalism. No, academic leftism now means ideological commitment to the shibboleths of antiracism, cross-sex fantasy, Marxist economics, and hatred of America. In defense of these ideas — all neatly contained, apparently, in the phrase “globalize the Intifada” (never mind that queer still is a slur in Gaza, Iran, etc.) — students can do no wrong. This explains why Barnard College President Laura Rosenbury (who was only inaugurated this February) lost a vote of no-confidence by her own faculty last week for attempting to balance the interests of free speech and civility on Barnard’s campus. God forbid that a college should be a place of learning and the civil exchange of ideas, rather than just a day camp for self-righteous activists. The students, of course, so high on their own supply of RightSideOfHistory, are too doped up to realize that they are being played by the adults who have nothing to lose; while the school can suspend or expel the students, the professors will go right on preaching the evils of settler-colonialism next semester.

An educational predicament

There is an odd slippage between Lewis’s critique of The Control of Language and my critique of the pro-Palestinian student protesters; education has since moved on from the oft-heard (and dubbed ‘conservative’) critique of 10 or 15 years ago about “multiculturalism,” under whose auspices students were told that no system of values was inherently superior to any other. Here’s Lewis:

…[T]he educational predicament of [King and Kelty] is different from that of all their predecessors. Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt. The reason why Coleridge agreed with the tourist who called the cataract sublime and disagreed with the one who called it pretty was of course that he believed inanimate nature to be such that certain responses could be more’ just’ or ‘ordinate’ or ‘appropriate’ to it than others. And he believed (correctly) that the tourists thought the same. […] Aristotle says that the aim of education is to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought…. Plato before him had said the same. The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting and hateful. (15,16)

There is a neat opposition between moral relativism and in a belief in objective value, which is what Lewis is defending in these three lectures.

It is the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others are really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are. Those who know the Tao can hold that to call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment, but to recognize a quality which demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not. (18-19)

But this is not the situation today; indeed, the debate (such as it was) over “multiculturalism” now seems downright quaint. Today, the stakes are so much higher — and not divided so neatly along the left/right political axis. Indeed, many life-long Democrats and before-it-was-a-slur proud liberals (like myself) are horrified by what moral relativism has morphed into: successor ideology.

Wesley Yang, who coined that term, described it thus in 2020 (edited for readability, emphases mine):

We have a basic problem with defining what’s happening within American institutions. Everyone who is a participant in those settings knows that we’re in the midst of kind of a bourgeois revolution, a sort of bourgeois moral revolution, in which certain foundational liberal values concerning free speech, due process, the presumption of innocence, and so forth, have come to be seen increasingly as obstacles to the path of the attainment of a particular vision of justice that’s being articulated and pursued by the activist classes whose ideas — once confined to obscure pockets of academia — have increasingly become sort of mainstream through the media and through social media as a part of the parlance of everyday life that affects those who are operating within those settings.

There’s a number of different ways to refer to it. Often, it’s heavily positively or negatively valenced. So a term like ‘social justice’ is sort of an attempt to identify the cause with justice as we all understand it, justice as such. A term like ‘identity politics’ is a little more neutrally valenced, but it doesn’t actually encompass everything that comes under the rubric of what we see happening right now….

I was writing a [Twitter] thread where I described some implicit bias training [required by] the New York City Board of Education… There was a screenshot listing some of the premises underlying this training, a description of white supremacy culture and the various facets of it. White supremacy culture was characterized as consisting of perfectionism, a sense of urgency, worship of the written word.

The more you went into it and you started to break down both the internal inconsistencies of some of these ideas, but also recognizing the provenance of them, you saw that there were ideas taken from anti-colonial studies, from post-colonial writings, from a black-nationalist-inflected approach that sees whiteness itself as a form of oppression of non-white people.

I ended up saying: what’s being encoded here is so diverse (and in many cases, so internally incoherent) and yet all of these different activist movements are moving together under a single umbrella and we need a word for it. And the word would be one that was as vague as the movement itself, [such as] ‘the successor ideology.’ Because we are in the midst of a kind of ideological succession and the succession is one that makes reference to and often sort of masquerades as being consistent with the liberal principles of fairness and tolerance out of which it grows.

The problem presented by The Control of Language is, in Lewis’s words, that “the very possibility of a sentiment being reasonable—or even unreasonable—has been excluded from the outset” (20-21). This is, clearly, a rather useless critique of social justice warriors, who are only too happy to declare as an objective value that everything Western (aka “white”) is bad. The moral relativism of “multiculturalism” has been replaced by a moral certainty; indeed, I am tempted to claim that the kumbaya West-isn’t-best attitude was in fact a parenthesis inside the Western tradition, rather than an actual evolution of it.

To understand this strange continuity between the world of Lewis’s Tao and successor ideology, you have to understand the liberal tradition as a corrective to the political misfortunes of the Western tradition. It turns out that when objective values combine with worldly power, conflict is the result. The American experiment to use a guarantee of free speech and non-denominational governance to avoid both tyranny and sectarian conflict was not a thought experiment — it emerged directly from experiences of religious war and all-powerful monarchs who could have your head if you didn’t pray the way they said to. These aspects of what we call liberalism came from the exhausted recognition that if you want to stop fighting about religion, you have to stop fighting about religion.

And yet it turned out that this was somehow not enough; the wars of religion were long settled by the time communism, fascism, and Nazism combined to produce the bloody horrors of the 20th century. The millions upon millions dead were interpreted (correctly) as a judgment on the West; indeed, it was the dangers of propaganda — think Hitler’s speeches — that motivated authors like King and Kelty to attempt to educate students not to be seduced by sentiment. In short order, though, it became all to easy to argue that all that had happened was not a function of the loss of the Judeo-Christian values but because of them. Turns out, if you teach children that the worst thing is a Nazi, and that Nazis do bad things, anyone declared bad is automatically a Nazi. This is how the very victims of the Shoah are now made equivalent to their murderers in the name of ‘human rights,’ a slogan that instead of upholding the old values (which are not just Western, as Lewis’s choice of the Chinese word Tao evidences), reduces them to an endless series of services that should appear as if by magic, separate of any individual or even collective responsibilities. When a PhD student at Columbia University feels inclined to describe food for criminal trespassers as ‘humanitarian aid,’ she is speaking the language of human rights.

Reality bites

I read another example of turning way from childish things recently. In The Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability, author (and activist) Lierre Keith describes how becoming a vegan as a teenager destroyed her physical and mental health. But she kept at it nonetheless for 20 years because she wanted so desperately to believe that it was possible to live without killing.

Nature is no more moral than it is immoral. It’s amoral, by definition. Life is literally a process of one creature eating another, whether it’s bacteria breaking down plants or animals, plants strangling each other, animals going for the throat, or viruses attacking animals. “All of nature is a conjugation of the verb ‘to eat’”, in the words of William Ralph Inge.

The paradigm that asks us to reject death certainly provides a simple ethical code, a code that can rally the righteous, but it is the black-and-white thinking of a child. The tremendous moral vigor that is the gift of youth seems to demand such rules, but they are essentially slogans and ethical platitudes, which are the root of fundamentalism. Adult knowledge demands more, starting with more information, and it includes the ability to incorporate that new information, to recast as necessary the behaviors informed by our values. Adults don’t just absorb, they learn. The challenge of adulthood is to remember our ethical dreams and visions in the face of the complexities and frank disappointments of reality. (74, emphases mine)

Yet we are now a culture that seems not just contented with black-and-white thinking, but also a culture that has literally pathologized the process by which children mature into adults — puberty. Though the tide seems to be slowly turning at long last, medical organizations of the US are still dominated by people who not only think that it is possible to be ‘born in the wrong body,’ but that any child who claims this applies to her should be immediately affirmed and then — in the absence of any physical disease whatsoever — treated pharmacologically to prevent her from maturing. Peter Pan used to be a story — now we have many living examples of young people who have reached the age of majority but who have never gone through the brain-maturing changes of natural puberty. It was always true that some kids were reluctant to grow up — but a world in which we deny them the ability to do so is a fresh hell of our making.

There is, as many are beginning to see, a connection between objective values and objective reality, one that does not allow us to abandon the former but preserve the latter. Keith writes:

The ancient world of the West saw the earth and the cosmos as a living body, and even into Christian Europe there were still religious strictures against human harm to the earth. But humanism removed those last restraints on human activity by killing off God, and replacing the metaphor of a body with that of a machine. The world has been dying at an exponential rate ever since. Kinda hard to call that progress. (71)

If we do not understand that there are givens, including that there is no life on earth without death, we will inevitably mistake the earth for what it actually is not: a machine. Just think: in our childish fantasy to live without killing, we will have actually destroyed our own world! Adults are those capable of abandoning the facetious moral rigor couched in the credo “meat is murder.” “Eventually,” Keith writes, “we see our only choices: the death that’s destroying life or the death that’s a part of life” (74).

Paul Kingsnorth, a longtime environmentalist who converted to Orthodox Christianity in 2020, makes the same observation about the essential relationship between the Tao and our continued humanity in his latest piece “Die Before You Die”:

We have long since taught our children that there is no God. Now we are teaching them that there is no humanity either. That their bodies can be changed at will into anything they like. Soon there will be no men and no women. Babies will be bred in artificial wombs. There will be no marriage and no family. Words like mother and father will be mocked or anathemitised. The algorithm will make sure of it. There will be nothing in the forest, nothing in the sea, nothing in the heart or in the spongy canals of the brain that cannot be remade into the new shape.

Kinda hard to call that progress, don’t you think?